Protected: Boston Background & History Part 2 – Independent Development through the Boston Massacre

Freedom Trail Ultimate Tour & History Guide – Touring & Suggested Itineraries

Select your language to auto-translate:

Self-Guided or a Tour?

So, should you take a guided tour or guide yourself? This book contains virtually everything a paid guide will share (actually, a lot more), and allows you to go at your own pace. With the free companion apps, or those available from the National Park Service (covers only the 16 official stops, but is very good, download here), you can have a wonderful visit. However, a group tour can be a lot of fun and may engage you in a way that a self-guided tour will not.

There are excellent free tours given by National Park Service (NPS) rangers. Most of the paid guided tours cost $12-15 per adult (some have senior discounts) and $8-10 for children.

Most tours run an hour or an hour and a half and concentrate on selected parts of The Freedom Trail – such as the downtown portions (Boston Common to Faneuil Hall – Stops 1 – 11), the North End (Paul Revere House, Old North Church & Copp’s Hill – Stops 12 – 14 ), or Charlestown (USS Constitution and Bunker Hill – Stops 15 – 16).

Within these time constraints, the guided tours do not allow you to spend much time within any of the Stops and will often not enter the Stops at all. Almost all will skip entering those Stops that charge a special admission fee (Old South Meeting House, Old State House and the Paul Revere House).

Recommended tour companies include:

National Park Service. The National Park Service (NPS) provides free ranger-guided tours and lectures including two 60 minute tours of The Freedom Trail (one covering downtown, the other the North End – combine them for a more complete visit), the USS Cassin Young, USS Constitution, and Faneuil Hall. They are highly recommended, well done, and the price is right. Some tours are attendance limited and first come, first served, so get there in time to get an admission sticker, usually 1/2 hour before the scheduled start. Call (617) 242 5642 (617) 242 5642 for information. For web-based tour information and times, click here.

(617) 242 5642 for information. For web-based tour information and times, click here.

The Freedom Trail Foundation. The Freedom Trail Foundation is the official voice of The Freedom Trail, and some of the proceeds from their tours goes to support the Trail. They offer a variety of quality tours given by costumed actors. For web-based information, click here.

Boston By Foot. Boston By Foot is a non-profit organization that uses unpaid volunteer guides that are well trained and have in-depth knowledge. They offer a variety of tours, including some geared to children. You do not need an advance ticket, just show up and pay the guide. Their approach is more in depth than many other companies, and they are very good. For web-based information, click here.

There are many other quality tour companies, some with specially tours such as for photographers or historic pub crawls. Search Google for “Boston Walking Tours” or TripAdvisor for “Freedom Trail, Boston.”

Suggested Itineraries

The entire Freedom Trail is only 2.7 miles, but seeing it all in one day will be difficult, especially if you want to spend time visiting any Stop. To help you plan, I’ve provided a quick assessment of each of the official 16 Stops, its significance to the Revolutionary period, and the recommended time needed for a visit.

Beneath the Stop Review section below, you will find itinerary recommendations with alternatives for 1/2 day and full day self-guided visits. For a two day visit, combine two of the day or four of the 1/2 day itineraries. Most of the downtown Stops (1 through 11) are close together. If including a guided tour, plan accordingly based on what that tour covers.

Walking directly from Boston Common to Faneuil Hall is only about .6 miles (1 km) and takes less than 15 minutes. Walking from downtown Stop 11 (Faneuil Hall) to Stop 12 (Paul Revere House) in the North End takes 10-15 minutes. The Charlestown Stops are another 15+ minute walk from the last Stop in the North End (Copp’s Hill Burying Ground), and there is a 10+ minute walk between the USS Constitution and Bunker Hill. There are no MBTA stations convenient to the Charlestown Stops.

Stop Review:

Stop 1 – Boston Common. A great old park, but unless you want to walk around and enjoy the outdoors, there is not much of prime historical importance to see. There is a good playground for younger children at Frog Pond.

Stop 2 – The State House. There are excellent guided tours and it is a fascinating and elegant old building, Plan 1.5-2 hours to pass through security and take the tour. While it is worthwhile, there is not much relating to the Revolutionary period as the State House was built after the Revolution. Take the time to view St. Gauden’s Robert Gould Shaw & MA 54th Memorial across the street at the edge of Boston Common.

Stop 3 – Park Street Church. Closed for viewing except during the summer. Unless you take a tour, it will not take much time. There is little of primary Revolutionary significance.

Stop 4 – Granary Burying Ground. This is the final resting spot for Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Paul Revere, the Boston Massacre victims, Mother Goose and others. Plan about 15 minutes to walk through.

Stop 5 – King’s Chapel. Great old church usually open for viewing. Plan 15 minutes to walk through, more if taking the fun Bell & Bones tour.

Stop 5a – King’s Chapel Burying Ground. The oldest in Boston, plan about 10 minutes to walk through and view the old stones. Not much of Revolutionary significance as the Burying Ground was full well before 1700.

Stop 6 – Boston Latin, Old City Hall, Franklin Statue. Everything is outside (there is no interior viewing of Old City Hall). Plan 5-10 minutes to view the outside plaques. If you want to see the Province House steps, plan for another 5 minutes to walk up Province Street.

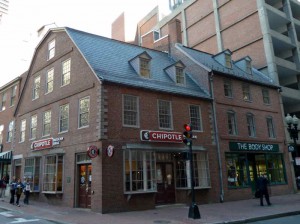

Stop 7 – Old Corner Book Store. You will walk by and see the house, which now houses a Chipotle Mexican Grill. Nothing to tour.

Stop 8 – Old South Meeting House. Plan 1/2+ hour to view inside and the exhibits. The Meeting House is interesting given the number of important Revolutionary-era meetings that took place here. There are interpretive exhibits that place the building and its events in history and a good three dimensional map of Revolutionary-era Boston that highlights key locations – fascinating given the city’s changing topography. Check their web site for other programs. Benjamin Franklin’s birthplace and the Irish Memorial are directly across the street and are quick to see.

Stop 9 – Old State House. The Old State House features excellent docent-given tours and talks that cover the building and Revolutionary events. The museum has some good displays and exhibits. Plan about an hour or more to visit and take a tour. Highly worthwhile.

Stop 10- Boston Massacre Site. This is a plaque embedded in the street directly below the balcony of the Old State House. This is a walk-by with a photo opportunity.

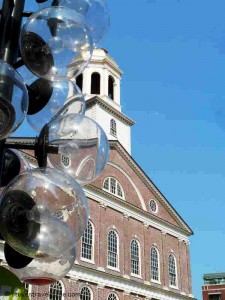

Stop 11 – Faneuil Hall. This is a great old and important building. Go inside and enjoy a ranger-led talk (given every 30 minutes). Plan for 30-45 minutes to visit the Hall. The Faneuil Hall Marketplace (Quincy Market) is located next door, and is a good place to stop, get something to eat or shop. Plan accordingly. The new National Park Service Visitor Center is located on the first floor of Faneuil Hall.

Note: From Faneuil Hall, it is a 15 minute walk to the next official Stop, the Paul Revere House, in the North End. On the way, you pass some interesting unofficial Stops in the Blackstone Block area – the Holocaust Memorial, Union Oyster House, Marshall Street, and the Ebenezer Hancock House. The Blackstone Block is also a good, less commercial place to take a break or to eat. Some of the local restaurants feature good lobster specials at lunch.

Stop 12 – Paul Revere House. Built in 1680, it is the oldest structure remaining in Boston. It is a good example of a period dwelling and you will gain insights into Paul Revere’s life. The costumed docents provide interesting descriptions of the house and the Revere family. Visiting is worthwhile, but the house is small, consisting of only four rooms. Plan for about 1/2 hour.

Note: It is about a 10 minute walk through the North End to the next stop. The North End is also an excellent place to stop for lunch. It has a very European feel and many wonderful restaurants.

Stop 13 – Old North Church. A beautiful and important church, the oldest remaining in Boston. A walk through takes 15 minutes, the worthwhile Behind-the-Scenes tour another 30.

Stop 14 – Copp’s Hill Burying Ground. A 5 minute walk up hill from the Old North Church. Plan about 10-15 minutes to walk through the Burying Ground. There are a few interesting graves, a headstone used by the British for target practice, and a nice view of the harbor.

Note: From here there is another 15+ minute walk across the bridge to Charlestown and the next Stop, the USS Constitution.

Stop 15 – USS Constitution and the Charlestown Navy Yard. Visiting the Constitution and the Museum can easily be a half day visit. For the Constitution alone, plan at least an hour to pass through security, view the small museum and take the guided tour of the ship. The very good USS Constitution Museum (different from the small museum attached to the Constitution), is worth another hour. A walk around the WWII Destroyer USS Cassin Young will take another 1/2 hour. Walking around the Navy Yard area is also a pleasure; there is only one restaurants in the Yard. This is a highly worthwhile 1/2 day, especially for children, who will enjoy exploring the ships.

Note: There is another 15 minute walk between the Charlestown Navy Yard and the Bunker Hill Monument and Museum. For a historic lunch, try the Warren Tavern, which is only a short detour between the two sites.

Stop 16 – Bunker Hill Monument. To tour the monument area, plan about 15-20 minutes, unless you plan to make the 294-step ascent to the top. That is a fun activity and provides a spectacular view of Boston and the surrounding area. If climbing the Monument, plan 1/2 hour. To visit the Bunker Hill Museum, which is excellent and best seen before the monument, plan another 1/2 to full hour. The museum features exhibits on the battle and Charlestown history, and has Ranger-guided programs – great for children. If you have time, visit the Museum before the Monument. Highly recommended.

1/2 Day Tour Alternatives

Option 1: (Downtown) Walk by Stops 1 – 3, visit Stops 3 – 5, walk by 6-8, visit 9, walk by 10, and visit 11. Lunch and break at Faneuil Hall Market or the Blackstone Block area.

Option 2: (Downtown and North End): Walk by Stops 1 – 3, visit Stops 3 – 5, walk by 6- 10, visit 11, walk by 12, visit 13 and 14. Lunch and break in Faneuil Hall Market, the Blackstone Block or the North End.

Option 3: (Charlestown – USS Constitution and Bunker Hill): Visit Stop 15 USS Constitution (bypass the Constitution Museum and USS Cassin Young), visit Bunker Hill Monument and Museum. Lunch at the Warren Tavern or at the Navy Yard.

Option 4: (Charlestown, USS Constitution): Spend a full 1/2 day visiting the USS Constitution, the Museum, USS Cassin Young and walk around the Navy Yard. Lunch at the Navy Yard or across the Bridge in the North End.

Option 5: (A little Downtown, free ranger-guided tour, North End, USS Constitution – requires a lot of walking and tour-time coordination): Start at Stop 11, Faneuil Hall, and listen to the NPS Great Hall talk, take the NPS tour that goes to the North End, visit Stops 13 – 15, take the Water Shuttle back to Long Wharf.

Full Day Tour Alternatives

Boston and the North End: Walk by Stops 1-3, visit Stops 3-5, walk by 6-7, visit 8 and 9, walk by 10, visit 11, lunch or break in Faneuil Hall Market, the Blackstone Block or the North End, visit 12-14.

Charlestown: spend a full 1/2 day visiting the USS Constitution, the Constitution Museum, USS Cassin Young and walk around the Navy Yard, lunch around the Navy Yard or at the Warren Tavern, visit the Bunker Hill Monument and Museum.

If you want to visit the entire Freedom Trail in a single day, it is recommended that you combine Options 2 and 3. It will be busy and there is a lot of walking, but you will have a great time.

What would I do?

Without question, if I only had 4-5 hours, I’d recommend Option 5, especially with kids. This requires planning to fit in the National Park Service ranger tours, but is absolutely worth it. Start at Faneuil Hall and attend a Great Hall ranger talk (every 1/2 hour) and get a sticker for the ranger-tour that goes to the North End (currently at 12, 2 & 3 PM – stickers available 1/2 hour prior. Confirm times at the NPS visitor center.) After the ranger tour, visit Old North Church (Stop 13), walk through Stop 14, then walk quickly to Stop 15 and take the USS Constitution tour. Take the Water Shuttle back to Long Wharf (every 1/2 hour during non-commuting hours). Grab lunch where you can.

If I only had half a day, wanted to self-guide, and could not coordinate times for Option 5, I’d recommend Option 2 with a lobster lunch in the Blackstone Block. See as much as you can, and the North End has fantastic character and a European feel. Don’t miss a Faneuil Hall tour or a visit to the Old State House. If you are not from New England, the lobster is not to be missed.

If I had a full day, combine Options 2 and 3. The downtown stops are great and I love the Navy Yard and USS Constitution (it is easy to spend too much time here). Bunker Hill and the Bunker Hill museum are excellent. Have a lobster lunch in the Blackstone Block or grab some character and a Paul Revere Burger at the Warren Tavern in Charlestown (I’d choose the lobster, but it may be too early in your day).

Great Side Trips

In my work with travelers at the National Park, I most often get asked about side trips to Harvard Square, Lexington and Concord. Visitors should also consider the wonderful Adams National Historical Park in nearby Quincy, especially if you have seen the HBO mini-series. The Harbor Islands are a joy – lots of fun, plenty to do, and a great diversion from city activities; not to mention a wonderful ride through the harbor. Go if you have time.

All of these destinations are reachable by public transportation (although getting to Lexington and Concord does take a little work) and can be visited in 1/2 day; although a visit to both Lexington/Concord and the Minuteman NHP requires more, and is worth it. If I only had 1/2 a day, I’d recommend a Harvard Square walking tour; but a close second would be the Adams NHP.

Freedom Trail Ultimate Tour & History Guide Introduction

Select your language to auto-translate:

Welcome

Congratulations on your Boston visit – whether for an afternoon, a day or two, a week, or more. Its a great city.

Boston has everything you want – world class museums, fantastic restaurants, shopping, sports, music, theater and history. Its a unique and charming place that can feed almost any passion. And, there are great options for any budget.

If you are interested in its history, especially The Freedom Trail and Colonial Boston, this Guide will help you make the most of your visit. It is full of insider tips, secrets and tricks not known by even the most ardent of professional guides.

For the most complete experience, Smartphone users should download the free companion apps – for Android, click here, or for the iPhone, click here. The apps are invaluable resources, are created specifically to work along side this Guide, or are equally usable as stand-alone apps for touring the Freedom Trail and historic Boston.

You will find everything you need to know about the official Freedom Trail Stops (there are 16 of them), interesting “unofficial” Stops, (I cover over 50 of them), and even the most interesting and historic restaurants. Maps, including an interactive, zoomable, photo-packed Google Map are included. To make the most of your visit, there are itineraries for one-half, one or two day tours.

In addition, I’ve included tips for the most worthwhile side trips to Harvard Square, Lexington & Concord, Adams NHP and the Harbor Islands. There is even a Budget Tips section – Boston is a big city, with big-city prices. There are many tips to moderate your visit’s cost without compromising the fun – and even include a lobster.

[For a YouTube video preview that includes the Stops and sites covered in this Guide, click here. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=A8TzQoOyibk) Keep your pause key handy as the video moves quickly!]

More than just a description of the Freedom Trail Stops, there is also the background history and information you will need to help you more fully appreciate what you visit.

All the information is provided at cascading levels of detail – from simple overviews to detailed descriptions of every Stop and events that include the Boston Tea Party, Paul Revere’s Ride, the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Choose just what you want to know, you can always return for more. Finally, there are recommendations for the best internet links and books, much of it free.

The influence Boston had on the thinking and actions that led to the American Revolution was extraordinary. Without Boston and its unique history, the American colonies break with Great Britain may have still happened, but not when and how it did. The Guide brings this to life and helps you to appreciate Boston’s really amazing impact.

Even though I’ve been a Bostonian since 1970 and have always been interested in history, there were three “ahas” that developed as I wrote this Guide. Understanding these helped me appreciate The Freedom Trail much more. They may be of interest to you, and they just might help your visit be more fun.

1) First, Puritan philosophy is at the root of the thinking that led to the American Revolution. Everyone knows that the Puritans who founded Boston left England seeking religious freedom, but they also brought with them their own brand of powerful ideas. Around those ideas they molded a unique religious, democratic, and fiercely independent society that hated outsiders (like the British) telling them what to do. These ideas shaped the leaders that shaped the Revolution – including Ben Franklin, Samuel Adams, John Adams, John Hancock, and Paul Revere.

2) Second, Boston’s Puritans were able to establish and run their own society only because England neglected them for three generations. By the time England tried to reassert control, it was too late, and they bungled the efforts they did make. The tension, disputes, and outright fighting between the Puritan New Englanders and the Anglican English is the essence of most of the Freedom Trail sites.

3) Third, Boston’s Colonial-era topography played a critical role in historical events. What you visit today is over 50% landfill and many of its hills have been leveled. Places you will walk, such as the area around Faneuil Hall, were actually part of the harbor when Boston was founded. Boston was practically an island – dependent on the harbor for its economy and supplies. When the port of Boston was closed after the Tea Party in 1774, until the Siege was lifted in 1776, the city was completely isolated. Understanding this will provide extra meaning.

The Freedom Trail

The original idea for The Freedom Trail was conceived by William Schofield, a long-time journalist for the now defunct Boston newspaper, the Herald Traveler. In 1951, Schofield had the idea for a walking path that connected Boston’s great collection of local landmarks. With the support of local historians, politicians and businessmen, the Freedom Trail was born.

The Freedom Trail is a 2.7 mile red brick path (mostly brick – some lines are painted) that connects 16 significant historic sites, referred to as “Stops” throughout the Guide. It starts at Boston Common and officially ends at the Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown. Most of the Stops are free and many are handicapped accessible, but some may be difficult to navigate for non-walkers. For the few that charge admission, there are discounted tickets available (see the Budget Tips section).

In addition to the official Stops, there are many other interesting things to see and experience near the Trail. These unofficial Stops are often directly related to The Freedom Trail and Colonial Boston, but some are simply interesting places. I’ve made every effort to cover everything relevant in the Guide – if you think I’ve missed something important, please email me and I’ll note it in an update to the custom Google Map and app that compliment the Guide.

Enjoy, Boston is a great city and The Freedom Trail is a national treasure.

How to Use the Guide

The Guide is best read on a Kindle, Nook, iPad, other eReader/tablet, or Smartphone. All important information, including maps, is embedded within the document.

The Guide can provide a more comprehensive experience, however, when read “live,” e.g., connected to the internet. When live, you have access to additional detailed information, including zoomable Google maps, video, and other items to enhance your visit. Embedded within the Guide as well as in the External Links & References section, there are links to the best and least commercial information available. You may wish to download and print selected materials prior to your trip.

If you are using the Guide as your personal tour guide when visiting The Freedom Trail, almost everything you need is provided within the section about any specific Stop. Essential information, including a high-level Stop description, operating hours, costs, phone numbers, web sites, and public transport information is in each Stop’s “Overview” section. More detailed Stop information is in each Stop’s “Background Information” section. Hyperlinks to related information elsewhere in the Guide are embedded. “Unofficial” Stops are listed with the closest official Stop.

The most significant background historical information is found in the Time Line, Boston History and North End sections. If you are reading the eBook for context, it is recommended that you start with those sections.

Budget Tips and the Historic Restaurant Guide are provided at the end of the eBook along with sections on Sources and recommended Related Information.

Hyperlinks to references within the book are generally provided as part of the text. To enhance the Guide’s usability on Smartphones and mobile devices, and there are links back to the Table of Contents at the end of each section. Links to external web-based references are always noted as requiring web access, so that if you are not internet connected you can avoid the unnecessary distraction or data fees.

In the spirit of keeping this Guide small, most of the images are compressed and enhanced for eReader viewing. In the Sources chapter, there are links to the original maps and illustrations so that, if desired, they may be viewed in their original, higher resolution formats.

Free Companion Apps, Maps, & Getting Around

I have created free companion apps for this guide which includes additional information and sites. There are even optional pre-translated versions (via Google-translate) available for download in Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Chinese and Japanese. The optional version also includes 35 additional points of interest in and around Boston. To download the app on Google Play, click here; to download the app for the iPhone, click here.

Below is an extract from one of the most illustrative maps available for The Freedom Trail, the “Park Map with Outline of 1775 Boston Shoreline” from the National Park Service. It is strongly recommended you download this along with the other excellent free maps from the National Park Service website, here. To download this map alone (it will download to your device), click here.

If you have web access, the best map is a custom Google Map, created especially for the Guide, available on the web here. It is fully zoomable, interactive, has detailed touring information, links and photos about each of the official and unofficial Freedom Trail Stops, restaurants and other attractions. The Google Map is a living map – it is being enhanced as I learn more and get tips from readers. It is the perfect companion to this Guide.

If you prefer to pick up paper maps once you reach Boston, they are available at either of the National Park Service Visitor Centers. There is a brand new Visitor Center in the first floor of Faneuil Hall (Stop 11) and one in the Charlestown Navy Yard, right next to the USS Constitution. For web access to the Visitor Centers, click here.

Maps and other tour information can also be obtained at The Freedom Trail Visitor Center on Boston Common (Stop 1). This is run by the Freedom Trail Foundation. For access to the map from their website, click here.

Boston is a walking city, and it is strongly recommended that you walk or take public transportation. Boston has the MBTA, the oldest subway system in the United States (called the “T” by locals). There are T stops close to most of The Freedom Trail Stops, although the Charlestown and North End Stops require moderate walks from the closest station. For a T map and schedules, click here. I’ve included public transportation references in the Overview section for each Freedom Trail Stop. You can also see public transportation references when using the Google Map referenced above.

Auto-Translate the Guide to Foreign Languages

For readers who prefer to read the Guide in a different native language, including Spanish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Mandarin and others, I’ve implemented a web-based auto-translate feature. Selecting an “auto-translate” link (embedded in the Guide’s text) will take you to a web page. Just select the language you want by clicking on a flag and view the translated text.

All translations are performed by a standard web-based translation engine, so it may take a second or two to process. And, the translation may not be perfect. But if you don’t read English well, this can help you enjoy more of your Freedom Trail visit.

Auto-translate is available for the Introduction and Touring & Itineraries, Boston Background & History, North End and Budget Tips chapters as well as for the Overview sections of each official Stop.

The first time you access auto-translate links for the Boston Background & History chapter, you will need to enter a password. The password is the first word of the third paragraph in that chapter – be sure to capitalize the word correctly. When using the auto-translate version, the chapter is broken into five parts for easier reading.

Updates, Supplemental Information & Print Version Discount

Additional and supplemental information, new maps, book updates and corrections are available from my website here. I write frequently about Historical Boston and the Freedom Trail, so be sure to check to see what is new.

For readers who want a print version of the Guide (can be easier to use when walking and is a great souvenir), which also contains over 30 additional photos and illustrations, it can be ordered at Createspace at a 25% discount (use code EZL2A2N3 when checking out). Alternatively, it is available at many of the Stops on the Freedom Trail, and at Amazon, website here.

Faneuil Hall – Freedom Trail Stop 11 Overview

Select your language to auto-translate:

The Cradle of Liberty

Given to the town by wealthy merchant Peter Faneuil in 1742, the Hall was host to many important Revolutionary-era meetings and events including speeches by James Otis and Samuel Adams, the establishment of the first Committee of Correspondence, and the first meeting to protest the tea tax that led to the Boston Tea Party.

Free The first floor is home to the National Park Service Visitor Center.

Open daily, 9-5 except during events; Ranger talks every thirty minutes.

Official website: http://www.nps.gov/bost/historyculture/fh.htm

617-242-5642

Handicap ramp and elevators are at the south side door near the Bostix booth. Enter through the Visitor Center.

Restrooms are in the basement and 2nd floor.

Public transportation: Green or Blue line to Government Center.

The Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, the oldest chartered military organization in North America, has a museum on the 3rd floor. Website: http://www.ahac.us.com/

Be sure to attend the Ranger talk if your time permits. Allow at least 1/2 hour for your visit. The Quincy Market area next to Faneuil Hall is a good place to shop, eat, and wander. In nice weather there are street performers, and it is one of the most visited areas in Boston.

.

Background Information

As you approach Faneuil Hall from the Old State House, you will see a bronze statue of Samuel Adams (pictured above). This represents Adams as he defiantly confronted British Governor Hutchinson after the Boston Massacre. Before being moved here, the statue stood in Adams Square, which was demolished to create Government Center.

At the base of the statue, there are a number of markings in the pavement that represents the harbor’s water line in 1630. All the land from here to the current harbor has been filled-in.

Faneuil Hall was given to Boston by Peter Faneuil (1700-1743). Peter was the son of Benjamin and Anne Faneuil, wealthy French Huguenots(Protestants) who, along with Peter’s uncle Andrew, fled from religious persecution in 1685. Peter’s father died when he was 18. Uncle Andrew, a shrewd merchant and real estate investor, became one of the richest men in New England.

On his own, Peter became a successful merchant running a triangular trading operation shipping slaves from Africa to the West Indies in exchange for the molasses used to make New England rum. Boston and New England was the world’s largest rum producer during the colonial period.

In addition to his own success, Peter inherited a significant fortune from his Uncle Andrew. It is interesting to note that his Uncle’s estate came with the stipulation that Peter never marry. Peter accepted the conditions and remained a bachelor.

Uncle Andrew died in 1738 when Peter was thirty eight. Unfortunately, Peter was only able to enjoy his increased fortune for five more years as he was to die of dropsy (edema) when he was only 43. He did live well during his remaining time, living up to the name of one of his ships – The Jolly Bachelor. He left behind a cellar full of fine wine, cheese and beer.

The town’s decision to allow Faneuil Hall to be built was not without controversy. Even though Boston was a major seaport by the early 1700s, it did not have a large central market. Although a central market was a normal feature of English towns and would simplify things for most merchants, many vendors opposed developing the market. They believed that if their stalls were centrally located, it would lead to increased price competition.

In 1740, Peter proposed to build the central market for the town at his own expense. His proposal was not universally popular and passed by only seven votes, 367 to 360.

The original design had stalls facing out on all four sides – waterfront, fish market, hay market and sheep market. To help appease the opposition, Faneuil added a meeting hall above the market space.

Work began September 1740 and was completed in September 1742, only six months before Peter’s death. The first public use of Faneuil Hall was for Peter’s funeral, in March 1743. The building suffered a major fire in 1761. When it was rebuilt in 1762, the meeting hall was enlarged.

Quincy Hall & Faneuil Hall in 1838 (Note the Waterline)

Faneuil Hall received a major expansion between 1805 and 1806 based on Charles Bulfinch’s design. Both its height and width were doubled, and the cupola was moved to the opposite end of the building. The open arcades that served as the market areas were enclosed. Between 1898 and 1899 the building’s combustible materials were replaced.

One original fixture of the building is the grasshopper weather vane on top of the cupola. This was created by Shem Drowne, and is from copper and gold leaf with glass doorknobs for eyes. It was stolen in 1974, but was later found hidden in the cupola’s eaves wrapped in some old flags.

The grasshopper became such a Boston icon that it was used during the War of 1812 to screen for spies. If someone claimed to be from Boston and they did not know about the weathervane, they had to be a spy.

As a political venue, Faneuil Hall has more than earned the name “Cradle of Liberty”. During the Revolutionary period, it was the site of many important political events. In May of 1764 it hosted the first protest over the Sugar Act. Rallies were held here against the Stamp Act (1765), the Townshend Acts (1767), and the landing of British Troops that were sent to quell the associated disturbances (1768) – which ultimately led to the Boston Massacre in 1770. The funeral for Boston Massacre victims was held here.

Led by Samuel Adams, in 1772 the first Committee of Correspondence was established here. In 1773, Faneuil Hall hosted the first of the meetings to protest the tea tax. These meetings were so well attended they were moved to the Old South Meeting House.

During the British occupation in 1775 and 1776, it was a barracks for troops, then later a theater. In one incident, British General Burgoyne’s theatrical farce The Blockade of Boston was being performed at Faneuil Hall when it was interrupted by a small Patriot attack on Charlestown. It seems that the Patriots had learned of the play and precisely timed their attack to disturb the British performance.

After the war, Faneuil Hall continued to serve as a center of political activity. In the 1800s, it was a key rallying point in the anti-slavery movement, hosting abolitionists such as Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglas. Jefferson Davis, later president of Confederacy, spoke here in defense of slavery.

Faneuil Hall was also host to events in support of the women’s rights movement and temperance. It was the sight of John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s final campaign speech, made just prior to his election to the presidency in 1960. This tradition continues as the Hall hosts political debates and is a frequent campaign stop for both local and national politicians.

On third floor is the Armory Museum of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company. The Ancient & Honorable Artillery Company is the oldest chartered military organization in North America. Today largely ceremonial, it was founded in 1637 to protect the colony against Indian attack. The Armory, located here since it moved from the Town House (the predecessor to the Old State House) in 1746, holds relics from all periods of American history.

Quincy Market / Faneuil Hall Marketplace

When Boston incorporated as a city in 1822, the market around Faneuil Hall was not large enough to meet the city’s needs. Under the leadership of Boston’s second Mayor, Josiah Quincy III (a statue of Quincy stands outside of Old City Hall – Stop 6), Quincy Market was built to provide the additional market capacity. It was completed in 1826 and used initially as a foodstuff and produce shopping center. At the time of its construction, it was at the harbor’s edge. The North Market and South Market buildings, which stand on either side of Quincy Market, were built in the mid 1800’s.

By the middle 1970’s the whole area had deteriorated. It was revitalized as part of the preparations for the United States Bicentennial in 1976. Today, it is one of the busiest tourist destinations in Boston.

The Blackstone Block and the Holocaust Memorial

As you proceed down the Freedom Trail from Faneuil Hall (a left out of the front door), you will cross North Street and walk down Union Street towards the North End and the next Stop, the Paul Revere House. The intersection of North and Union Street begins the Blackstone Block – bounded by Union, North, Hanover, and Blackstone Streets. These streets were among the first streets to be laid out in Boston, and date from the 1600s.

On the grass mall just to left of Union Street, you will see the six glass towers of the Holocaust Memorial, established by survivors of the Nazi concentration camps. Each of the six towers represents one of the six primary Nazi concentration camps.

The towers are set on a black granite path, and glow at night. Each tower rises over a black chamber that emanates smoke from charred embers, creating an almost spiritual feeling. Six million numbers, suggesting the tattoos that were cut into those that perished during the Holocaust, are etched in glass.

This is a haunting and moving reminder of one of the greatest tragedies of our time.

You now cross Union Street from the Holocaust Memorial. The Union Oyster House on your right. The Union Oyster House is the oldest operating restaurant in the United States.

The Freedom Trail now winds down Marshall Street towards the North End. Marshall Street is one of the oldest and most authentically colonial streets remaining in Boston. On your right, just past the Green Dragon Tavern, is the Ebenezer Hancock House.

The Ebenezer Hancock House was built in 1767 by John Hancock’s uncle. John inherited it and gave it to his brother Ebenezer, who became the deputy paymaster of the Continental Army during the Revolution.

The Boston Stone, directly across from Ebenezer’s house, has been a landmark since 1737. A painter brought the stone from England to grind pigments prior to 1700. According to legend, it served as the “zero milestone,” used for measuring the distance to Boston – e.g., “20 miles to Boston” would mean 20 miles to this stone. The dome of the State House on Beacon Hill serves as Boston’s current zero milestone.

Proceed down Marshall Street, cross Hanover Street, and take a right towards to the North End. On Fridays and Saturdays you will pass through the Haymarket open-air market. There is a huge variety of fruits, vegetables, meats and seafood – all at bargain prices.

Haymarket Open Stall Market (open Friday & Saturday)

You may want to buy some berries to go with the pastries that will tempt you in the North End. Be careful of pickpockets.

Now cross through the Rose Kennedy Greenway to the North End. The Greenway is a series of parks that wind through the city covering the site of the Big Dig. An elevated highway used to bar the entrance to the North End (the trellis you see is at the height of the old highway). The Big Dig moved the highway (Route 93) underneath the city. So right now, you will be walking over Route 93

Bunker Hill Monument – Freedom Trail Stop 16 Overview

Select your language to auto-translate:

“The Whites of Their Eyes”

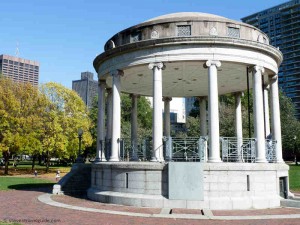

The monument is located on Breed’s Hill at the site of the Patriot redoubt during the Battle of Bunker Hill, which was fought on June 17, 1775.

Free

Daily 9 – 5; last climb at 4:30. July and August 9 – 6; last climb at 5:30

http://www.nps.gov/bost/historyculture/bhm.htm

617-242-5601

Handicap access to the lodge next to monument is via a ramp. The monument has 294 steps to the top.

Restrooms are in Bunker Hill Museum basement, across the street.

The Bunker Hill Museum (recommended – across the street), is fully accessible with elevators and restrooms.

Museum website:

http://www.nps.gov/bost/historyculture/bhmuseum.htm

Background information

Most visitors to the Bunker Hill Monument will stop at the Bunker Hill Museum, and we highly recommend visiting. Run by the National Park Service, the museum is just across the street from the steps to the base of the monument. It is excellent, featuring very well done interpretive displays and dioramas and ranger-led programs, which are often oriented to children. There are full bathroom facilities and it is handicap accessible. Everything is free.

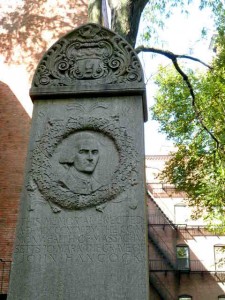

Proceeding across the street from the museum and up the steps to the monument, you will pass the statue of Colonel William Prescott (pictured above), Patriot commander during the battle. Some legends identify Prescott as the man who uttered “don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” Two superior officers were present at the battle, Major Generals Israel Putnam and Joseph Warren, but both declined to take command from Prescott.

The current obelisk is the second monument erected to commemorate the battle. The first was an 18-foot wooden pillar with a gilt urn that was erected in 1794. In 1823, the Bunker Hill Monument Association was formed by a group of prominent citizens who desired a more fitting memorial.

The 221-foot high monument is located on Breed’s Hill, at the site of the Patriot redoubt during the battle. The monument is constructed of granite from Quincy, Massachusetts – the same site that provided the granite for Dry Dock 1 in the Charlestown Navy Yard. A special railroad, the first common carrier in the United States, was built to haul the granite from Quincy to Boston. The final leg of the granite’s journey across the harbor was by barge.

Construction started in 1827 but was not completed until 1843 as there were many funding-related delays. To finish the project, the Monument Association actually had to sell off part of their original land, leaving only the summit of Breed’s Hill that you see today.

The small exhibit lodge adjacent to the monument was constructed in the late 1800s and houses a few statues and paintings, including a particularly good one of Doctor/General Joseph Warren. The Bunker Hill Monument Association maintained the monument and grounds until 1919 when it was turned over to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. In 1976 the monument was transferred to the National Park Service.

To ascend the 294 steps to the top of the monument, pass through the lodge and head up. It is recommended that you be confident in your ability to complete the round trip as there is no elevator and no place to sit down, except on the staircase. Climbers to the top will enjoy a great view of Boston and the surrounding areas.

Charlestown Navy Yard – Freedom Trail Stop with Old Ironsides

Select your language to auto-translate:

US Naval Facility Since 1800

The Charlestown Navy Yard is home to the USS Constitution, the USS Cassin Young, one of the first two dry docks in the US, and the USS Constitution Museum.

Great fun. Plan for a several hour visit.

The Museum is free, donation requested

Open 9-5 daily. Closed Christmas, New Year’s Day and Thanksgiving

National Park Service website:

http://www.nps.gov/bost/historyculture/cny.htm

National Park Service Maritime History website:

http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/maritime/bns.htm

USS Constitution Museum website:

http://www.ussconstitutionmuseum.org/

Museum phone: (617) 426-1812

Public transportation: Green or Orange line to North Station (in Boston proper). Alternative, 93 Bus to Sullivan Station Bunker Hill.

Plan at least an hour for a cursory view of the Navy Yard. If visiting the Navy Yard along with Constitution, plan 2+ hours.

If coming from downtown, the Water Shuttle from Long Wharf is an excellent and fun way to travel and see the harbor at the same time.

Background Information

In 1800, the government purchased the land for the Charlestown Navy Yard at Moulton’s Point, and established the yard itself shortly thereafter. (Moulton’s Point is where the British troops landed for their attack on the Patriots during the Battle of Bunker Hill.) In 1814, the yard launched the first US ship of the line, the USS Independence.

Multiple Navy Yard ships saw service in the Civil War – however, it was primarily a repair and storage facility until the 1890s. At that time, it started to build steel-hulled ships.

The Navy Yard reached its height of activity during World War II, with peak employment in 1943 of 50,128 men and women – working around the clock, 7 days a week. The yard then covered 130 acres with 86 buildings and 3.5 million square feet of floor space. A second dry dock was also added.

During this peak period, the Navy Yard could build a Destroyer Escort in four months and an LST (Landing Ship Tank) in less than four weeks. Overall, between 1939 and 1945, the Navy Yard built 30 destroyers, 60 escort vessels, overhauled and repaired 3,500 ships, and outfitted over 11,000.

After World War II, the Navy Yard was involved with upgrading the fleet and modifying World War II ships for Cold War service. Being so far from the fighting, the Navy Yard did not receive much work during the Korean and Vietnam conflicts.

As part of cost cutting measures, President Nixon ordered the yard closed in 1974. Many Bostonians believe the Nixon administration made that decision to punish Massachusetts, the only state to vote against him in 1972.

Since the closing, the bulk of the facility has been recycled and developed. The thirty acres that were transferred to the National Park Service became part of the Boston National Historical Park, with a mission “to interpret the art and history of naval shipbuilding.”

Dry Dock 1

Dry Dock 1 was one of the first two dry docks put into service the United States, missing out on the honor of being first by only a week – that distinction when to Norfolk, Virginia. Dry docks are important to avoid the tedious, expensive and dangerous process of careening or “heaving down” a ship to work on its hull. Careening requires leaning a ship over on its side, which puts great stress on its hull and only exposes one side at a time. In fact, sometimes ships would sink during the careening process.2

The need for dry docks was understood from the beginning of the US Navy, but construction did not begin until 1827 and then took six years to complete. The project was designed and under the control of Loammi Baldwin, considered the father of civil engineering in the United States.

The granite for this project, as well as the dry dock in Norfolk, came from Quincy – the same site that provided the granite used for the Bunker Hill Monument. Dry Dock 1 opened in June of 1833 and its first customer was the USS Constitution.

There are excellent interpretive displays that show how the dry dock works and illustrates the alternative careening method.

USS Cassin Young

The USS Cassin Young is a World War II Fletcher-Class Destroyer commissioned on the last day of 1943. She served with distinction in the Pacific, including during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. She received damage during two separate kamikaze attacks during 1945, one of which killed twenty-two and wounded forty-five sailors.

Visitors can tour the ship, with or without guides. ID is required.

The photograph in the Dry Dock 1 section above shows the USS Cassin Young.

Muster House

The interesting eight-sided Muster House was built in 1852 and was an administrative building for the Navy Yard. The clock and bell were used to assemble civilian employees for work at a time when most workers did not wear watches.

Rope Walk

Rope has always been is an essential element of ships, so having quality and production control was a key aspect of the US Navy’s strategic plan. The USS Constitution, for example, requires over four miles of rope.

The Ropewalk at the Navy Yard produced most of the cordage used by US Navy between 1838 and 1955 – in 1942 alone producing over 4 million pounds! It had a ¼ mile of rope-laying area, allowing it to produce rope of up to 1200 feet in length as rope is twisted in a straight line. Its innovative steam-powered machinery could produce rope of much higher strength than manual techniques. The Ropewalk was used until 1971.

Although the building is still standing, it is boarded up and there is not much to see. There are interpretive displays in the National Park Service Visitor Center that you walk through prior to boarding the USS Constitution. These explain the rope making process and illustrate the rope walk in operation.

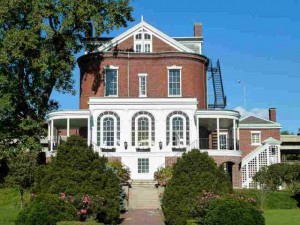

Commandant’s House

The Commandant’s House was built in 1805 and was home to the Navy Yard’s commanders and their families for many years. It has hosted five U.S. presidents and many dignitaries and foreign heads of state.

There are no visitors allowed inside.

USS Constitution – Freedom Trail Stop 15 Overview

Select your language to auto-translate:

Undefeated in 33 Fights

USS Constitution, or “Old Ironsides,” is the oldest commissioned warship afloat in the world.

Free admission, but visitors must show a valid ID and pass through security to visit the ship and enter through the National Parks Service Visitor Center. The Visitor Center has an introductory film and interesting exhibits that cover the Navy Yard and the Constitution.

Nov. 1- March 31 Tues-Sun 10-4; April 1-Sept. 30 Tues-Sun 10-6; Oct. 1- Oct. 31 Tues-Sunday 10-4; Closed for Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Years

A wait is usually required to take the worthwhile USS Constitution tour.

Official National Park Service phone & website: (617) 242-5601

http://www.nps.gov/bost/historyculture/ussconst.htm

Official USS Constitution website:

https://www.navy.mil/uss-constitution/

Handicap access to the ship is via a ramped gangplank to main deck. The deck has 1/2″ raised ridges. Navy personnel can assist. The lower decks are down steep staircases.

Restrooms are in the Visitor Center

Public transportation: Green or Orange line to North Station (in Boston proper). Alternative, 93 Bus to Sullivan Station Bunker Hill.

Plan at least an hour to view the Constitution, including a tour.

Background Information

The Revolutionary War officially ended in 1783 with the Treaty of Paris. In 1785, the United States sold its last remaining naval vessel due to a lack of funds. The same year, two American merchant ships were captured by Algiers.

Eight years later, in 1793, Algiers captured eleven ships and held their crews and cargo for ransom. The new nation was undergoing one of its first tests.

Waking up to the need to protect its interests, Congress authorized the Naval Act of 1794. This act allocated the funds to build six frigates that were to become the start of the US Navy. Four of the frigates were designed to carry forty-four guns, and two were to carry thirty-six guns.

The USS Constitution was the third of the six original frigates. She was built, starting in November 1794, across the river from its current berth, at the Boston shipyard of Edmund Hartt.

The Constitution’s design took into account the reality that the United States could not match the European states navies’ heavy “ships of the line.” The much smaller US Navy needed to be strong enough to defeat other frigates, yet fast enough to avoid fights with heavier ships.

Her design was unusual for the time in that she was very long and narrow, and mounted heavy guns. She also had a diagonal rib scheme for extra strength. The primary materials were pine and oak, including southern live oak from Georgia. Live oak is extremely dense, heavy and hard, and is the reason that the Constitution could survive heavy cannon shots without damage. This unique design was to be proven many times in battle.

Originally designed for forty-four guns, the Constitution was often equipped with fifty or more. During the War of 1812, she carried thirty 24-pound cannons on the gun deck (one level down from the upper deck), twenty-two 32-pound carronades (shorter range cannon) on the upper deck and two chase guns each at the bow and stern.

Peace with Algiers was announced in 1796, and construction was halted before any of the ships could be launched. Prompted by President George Washington, Congress agreed to continue funding the three ships closest to completion – the USS United States, Constellation, and the Constitution. The Constitution finally slipped into the waters of Boston harbor in October 1797.

The Constitution served briefly during the Quasi-War with France from 1798-1800. During this conflict, she served three tours of duty in the West Indies and participated in several actions. She returned to Boston in 1801 where she was put into reserve. Prior to her next duty service, her bottom was resheathed with copper from Paul Revere’s factory – the first copper rolling mill in the United States.

In 1803, under Captain Edward Commodore Preble, she sailed to Africa’s northern coast to confront Barbary ships during the First Barbary War. There she participated in multiple actions, the most significant being the Battle of Tripoli Harbor. She was on station during this conflict for over four years, not returning to Boston until 1807.

The Constitution’s most famous actions took place during the War of 1812. In August, about 700 miles east of Boston, the Constitution met the British frigate, the HMS Guerriere. Within about 35 minutes, the Guerriere was a wreck and too damaged to be salvaged. After transferring the wounded and prisoners to the Constitution, the Guerriere was set afire and blown up.

It was in this fight that the Constitution earned the nickname of “Old Ironsides.” When many of the Guerriere’s shots were observed to bounce harmlessly off her hull, an American sailor reportedly exclaimed “Hussah, her sides are made of iron.”

On December 29 of that year, the Constitution fought and defeated the HMS Java off the coast of Brazil. The Java was defeated in about two hours. As with the HMS Guerriere, she was too damaged to be captured had to be destroyed at sea.

The Constitution participated in several other actions, including the defeat of the HMS Pictou, and the capture of HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. The Levant was later recaptured by the British. The Constitution also had two cat-and-mouse escapes from superior British squadrons. She additionally captured a number of British merchant vessels.

After the War of 1812, the USS Constitution served in the Mediterranean squadron. This service was mostly uneventful, but there were notable discipline issues regarding the behavior of the crew while in port.

The normal service life for a ship during this period was ten to fifteen years. When the Constitution was thirty-one, a service order was put in to request money for repairs. Catching wind of the request, a Boston newspaper erroneously reported that she was about to be scrapped. Within two days, Oliver Wendell Holmes’ poem “Old Ironsides” was published. The ensuing public outcry incited efforts to save her, and the refurbishment costs were approved. The USS Constitution made the first use of Dry Dock 1.

Most of the Constitution’s subsequent duties were ceremonial. She ferried ambassadors ministers to new posts and performed various patrolling duties in the Mediterranean, South America, Africa and Asia. Just prior to the Civil War, she became a training ship.

There were attempts to make her seaworthy once again to attend the Paris Exposition of 1878, but these were unsuccessful. In 1881, she was deemed unfit for service. The Constitution was finally returned to the Charlestown Navy Yard in 1897.

In the early 1900’s, there were several attempts to refurbish her, but all failed. In 1905, the Secretary of the Navy suggested that she be towed out to sea and used as target practice. Public outcry prompted Congress to authorize $100,000 for her restoration. By 1907 she began to serve as a museum ship with tours offered to the public.

Since that time she has undergone multiple refurbishments and cruises, including a three-year, 90-port tour of the nation that started in 1931 and transited the Panama Canal in 1932. Her most extensive refurbishment was from 1992 to 1995. She sailed under her own power in 1997, in honor of her 200th birthday.

The Constitution typically makes one “turnaround cruise” each year during which she is towed out into Boston Harbor to perform demonstrations, including a gun drill. She is then returned to her dock, where she is berthed in the opposite direction to ensure that she weathers evenly. Attendance on the turnaround cruse is based on a lottery draw and is a highly prized ticket.

Old North Church – Freedom Trail Stop 13 Overview

Select your language to auto-translate:

The Steeple that Started the Revolution

In April, 1775, it was the sight of the hanging lanterns that notified Patriots in Charlestown that the British were leaving “two if by sea” prior to Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride and the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

Admission. Check for availability and rates: https://www.oldnorth.com/admission-pricing/ Separate admission for Crypt tour (worthwhile).

Sunday services 9 and 11 AM

http://oldnorth.com/

617-523-6676

Handicap access – there is a 1/2″ step at entrance to church; gift shop limited.

No restrooms in the Church

Public transportation: Green or Orange line to Haymarket Station.

Plan about 15 minutes to walk through.

Excellent gift store next to the Church.

.

Bckground Information

Old North Church, officially known as Christ Church, was begun in 1723 and took twenty-two years to complete. It is the oldest church remaining in Boston. On April 18, 1775 its place in history was cemented when Sexton Robert Newman climbed the steeple and hung the two lanterns that signaled to Patriots watching from Charlestown that the British were marching on Lexington and Concord “by sea”.

Old North was the second Anglican Church in Boston, after King’s Chapel. As an Anglican Church, the majority of its congregation was loyal to the British King and the membership included the Royal Governor. The King gave Old North its silver and a bible.

The fact that this is an Anglican Church makes its place in American history even more extraordinary as it made the use of the Church by Revere and Newman extremely risky. After hanging the lanterns, Newman had to escape out a window. (The original window through which he left the church was bricked up in 1815. It was rediscovered during restoration work in 1989.) Paul Revere was never a church member as he was a Congregationalist. He did, however, work here as a bell ringer.

Old North was modeled after the work of Sir Christopher Wren in London, perhaps using St. Andrews-by-the-Wardrobe in Blackfriars, London as the model. St. Andrews-by-the-Wardrobe was destroyed by German bombs during World War II, but has since been rebuilt.

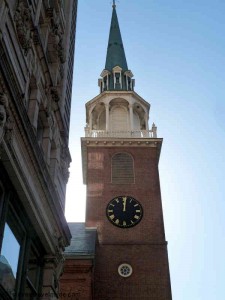

The original steeple was destroyed in a storm in 1804 and Charles Bulfinch designed the replacement, which stood until Hurricane Carol in 1954. The current steeple uses design elements from both the original and the Bulfinch version. The church steeple now stands 175 feet (53 m) tall, some sixteen feet lower than the original. At its tip, however, is the original weather vane.

The church bells, the oldest in America, came from England and date from 1744. They were restored in 1894 and again in 1975. They ring regularly, and are beautiful – check the website for the bell ringing schedule.

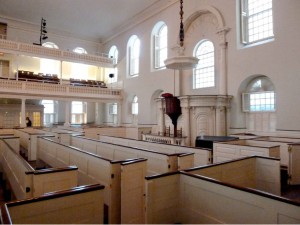

Many of the church details are original. The high box pews were purchased by congregation members in a manner similar to the way season tickets to sporting events are purchased today – buy first in the back and trade up when a better seat opens up. The pews high walls are designed to retain the warmth of hot coals or bricks placed on the floor. The chandeliers are from England.

The organ, built in 1759, still has some original components and is used. The clock was built by some of the parishioners in 1726. To the left of the pulpit there is a lifelike bust of George Washington that dates from 1815. During his visit in 1824, the Marquis de Lafayette, a key aid of Washington, commented on the extremely lifelike nature of the bust.

Old North’s basement holds some 1,100 bodies buried in 37 in crypts. It was used between 1732 and 1853, and each tomb is sealed with a wooden or slate door, with many doors still covered by the plaster ordered by the city in the 1850s (see in the Behind-the-Scenes tour).

The founding rector of the church, Timothy Cutler, was buried right under the altar. Also buried under the church is British Marine Major John Pitcairn, who was mortally wounded at the Battle of Bunker Hill and entombed with many others killed in that battle.

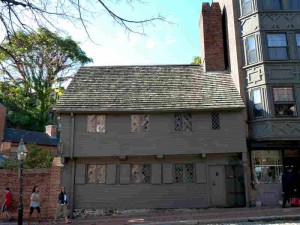

Paul Revere House – Freedom Trail Stop 12 Overview

Select your language to auto-translate:

Oldest Building in Boston c. 1680

This was home to the Revere family at the time of Paul’s famous ride to alert the Patriots of the British march on Lexington and Concord.

Admission.

Open year round. Check here for rates and times:

https://www.paulreverehouse.org/hours-prices/

(617) 523-2338

Handicap accessible first floor (about 1/2 of the small museum). Ask at the ticket booth for a temporary ramp.

No restrooms

Public transportation: Green or Orange line to Haymarket Station.

Interesting old house with knowledgeable guides, the last of its type in Boston. Some Revere relics. It is very small. Photography inside prohibited.

Plan 1/4-1/2 hour.

Background Information

The Paul Revere House in North Square is the oldest remaining building in Boston. It was built on the ashes of the Second Church of Boston’s (Old North Meeting House) parsonage, which was the home to Increase Mather and his family (including his son Cotton). The parsonage burned in 1676.

The original house dates from about 1680. Its first owner was Robert Howard. By the time Revere purchased the house in 1770 it had undergone significant changes with the front roof line being raised in the popular Georgian style and a partial third story added.

Revere moved in with his first wife, Sarah, his mother and five of his children. Sarah bore him a total of eight children, and he had another eight with his second wife, Rachel. Revere’s silversmith shop was a couple of blocks away.

Revere owned the house until 1800, but likely moved out as early as 1780. After he sold the house, it served as a tenement with its ground floor remodeled for use as shops.

The house was purchased by Revere’s great-grandson in 1902 to prevent its demolition. It then underwent restoration to an approximation of its 1700 appearance, opening in 1908 as one of the earliest historic house museums in the United States.

During the renovation, the roof line was restored to its original pitch, but without its gable. Despite the renovation, ninety percent of the house is original including the foundation and inner wall material, some doors, window frames, and portions of the flooring, foundation, inner wall material and raftering. All the glass has been replaced. Inside, there are several pieces of furniture believed to have belonged to the Reveres.

Adjacent to the Paul Revere house is the brick Pierce-Hichborn House, built about 1711 in the Georgian style. It was owned by Nathaniel Hichborn, a boat builder and cousin of Revere’s. It is also a nonprofit museum operated by the Paul Revere Memorial Association.

North Square, North Meeting House & Garden Court Street

The North Square is directly across the street from the Paul Revere house. It was the center of the North End life and commerce during Colonial times and the site of some of the town’s most impressive mansions.

It was also the site for the North Meeting House (Boston’s Second Church), which was first built in 1649, burned down in 1673, and rebuilt the following year. It was used by the British for firewood during the winter of 1775-76 during the Siege of Boston.

Just around the corner from North Square is Garden Court Street. This was the site of the Clark-Frankland and Thomas Hutchinson mansions. Rose Fitzgerald (Kennedy), the mother of President John F. Kennedy, was born at 2 Garden Court Street in 1890.

St. Stephen’s, Paul Revere Mall & Clough House

The Freedom Trail from Paul Revere’s house takes a left down Prince Streetand a right hand turn on Hanover Street. Proceeding down Hanover Street, just before you cross to enter the Paul Revere Mall, you will pass St. Stephen’s Church.

Saint Stephen’s is the last remaining Charles Bulfinch designed church in Boston. It was completed in 1804 as the New North Congregational Church. It became Unitarian in 1813, and in 1862 was sold to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Boston and renamed St. Stephen’s.

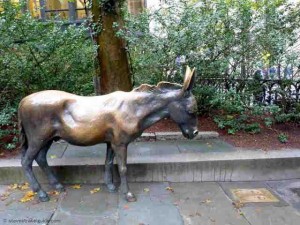

Crossing Hanover Street, you enter the Paul Revere Mall. The iconic statue you encounter (also on the cover of the Guide and at the start of the North End chapter) is by Cyrus Dallin. Dallin was a famous sculptor that worked in the nearby town of Arlington, MA. For my blog entry on the Dallin Museum, click here.

The Paul Revere Mall, also known as The Prado by locals, was created in 1933. It is a brick passage and park that leads from Hanover Street to the Old North Church. The mall walls are lined with bronze plaques that commemorate famous North End residents.

Clough House

At the end of the Mall, just before the stairs up to the Old North Church, is the Clough House, which dates from 1712. One of the oldest homes remaining in Boston, it was home to Ebenezer Clough, a master mason who helped build Old North Church. This is representative of many houses that once made up this neighborhood. It also houses an small but excellent historic printing museum, The Printing Office of Edes & Gil, website here. Check to see if it open.

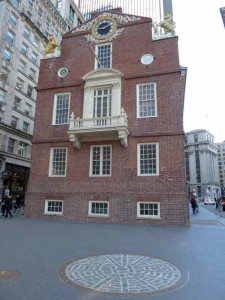

Old State House – Freedom Trail Stop 9 Overview

Select your language to auto-translate:

Oldest Public Building in Boston (1713)

The Old State House was the site of the British government offices until they left after the Siege of Boston in 1776, and the state legislature until 1798. It was the site of many important Revolutionary-era events

https://www.revolutionaryspaces.org/old-state-house/ (617) 720-1713

The current building replaced the first Town House, built on this site between 1657-68, burned down in the Great Fire of 1711.

It is now the home of the Bostonian Society and houses an excellent museum and docent programs.

Admission. Combined admission to the Old South Meeting House and the Old State House.

Open Daily, 10-5. Check for holiday hours.

The Old State House is not considered wheelchair accessible

Public transportation: Orange or Blue lines to State Street. Alternative, Green line to Government Center, or Red line to Downtown Crossing.

The talks given by museum personnel are excellent and run 20-30 minutes – covering subjects such as the Boston Massacre and Old State House History. The museum has interesting collections. Plan at least an hour for your visit.

Background Information

Boston’s first official town hall, called the Town House, was started in 1657 and dedicated in 1658. It was enabled when Robert Keayne willed £300 for a Town House with stipulations not only to size and construction, but also that it would contain a marketplace, a library, and serve as the home for the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, of which he was the commander. Keayne’s bequest was doubled by over 100 “Townesmen,” enabling the Town House to be built.

The first Town House served for the next 53 years until it burned down in the Great Fire of 1711. Within two years, the current Old State House was built. This building was gutted by fire in 1747 and reconstructed over the next three years.

The Old State House was to serve as the location for British Government offices until the British left Boston in 1776. In addition to the meeting chamber of the Royal Governor, the Massachusetts Assembly and the Courts of Suffolk County and the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Courts met here.

The Old State House was the site of many significant events leading up to the revolution, including James Otis’s impassioned argument against the Writs of Assistance in 1761. In 1770, the Boston Massacre took place just in front of the building.

Official proclamations were read from the balcony overlooking State Street (it was called King Street before the Revolution). On July 18, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was read from the balcony to a crowd of excited Bostonians. Soon after hearing the Declaration, the lion and unicorn, symbols of the British monarchy, were torn down. They were replaced during the building’s renovation in 1882.

After the Revolution, the Old State House continued to operate as the seat of Massachusetts government until the new State House was completed in 1798. The state then wanted to sell the building and share the money with the town. The town rejected the plan and instead purchased sole title.

The building was subsequently rented to a wide variety of businesses including cobblers, harness makers, and wine vendors. A bank tried to purchase it in 1822. For a period between 1830 and 1844 it became a Boston City Hall.

By the 1870’s it was dilapidated and an eyesore. The city of Chicago offered to buy it, tear it down and move it to Lake Michigan “for all America to revere.” Shamed by the proposal, in 1881 the Boston Antiquarian Club was formed, later incorporating as the Bostonian Society. The Society persuaded the city to save and restore the building.

Today, the Bostonian Society operates an excellent museum that features talks and tours. The museum displays artifacts from the Revolutionary period that include many of John Hancock’s personal possessions. It is a worthwhile stop.

Boston Massacre Site – Freedom Trail Stop 10

Select your language to auto-translate:

This was the site of the Boston Massacre, which occurred on March 5, 1770. The Massacre took place after an unfortunate chain of events led British soldiers to fire on an angry Boston mob, killing five and wounding six. Although hardly a massacre (most of the soldiers were later acquitted of blame), it was to be an important propaganda event in provoking Colonial unrest.

There is a plaque on the ground just beneath the balcony of the Old State House that marks the site.

This is a walk-by with a photo opportunity.

Old South Meeting House – Freedom Trail Stop 8 Overview

ParagraphAdd BWS ShortcodeOld South Tower Meeting House – Freedom Trail Stop 8 –

Select your language to auto-translate:

Home of Rebel Dissension

As Boston’s largest building in the Colonial period, Old South was the site of many important gatherings and became the emblematic home of the Patriot cause.

Admission. Combined admission to the Old South Meeting House and the Old State House.

Open Daily, 10-5. Check for holiday hours.

http://www.oldsouthmeetinghouse.org/

617-720-1713

Handicap access: wheelchair accessible, listening devices available

Public transportation: State Street (Blue/Orange Lines), Government Center (Green Line) and Downtown Crossing (Red Line).

Plan about 1/2 hour to view the interior and the exhibits.

For more about the Boston Tea Party, click here

Background Information

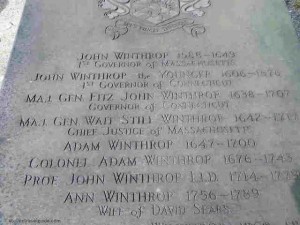

The Old South congregation was created when a group of dissenters split off from the First Church in 1669. Their original meeting house, a simple cedar sided building, was built on a part of what was the corn and potato patch of John Winthrop – the first Puritan leader. After Winthrop died, the land was owned by influential preacher John Norton. It was donated to the congregation by John’s widow, Mary.

The original meeting house was the site of Benjamin Franklin’s baptism, which took place on a wintry night in January of 1706. The first meeting house was torn down in early 1729. The current structure, based on Christopher Wren’s work in London, was dedicated in April of 1730.

The new meeting house was the largest building in Boston and was host to many significant meetings. As the conflicts with England amplified during pre-Revolutionary years, it became known in London for its role as a key place for Colonial protests. Almost every significant Patriot leader held court here – including James Otis, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Dr. Joseph Warren.

Perhaps the most famous meetings associated with Old South are those that preceded the Boston Tea Party. At the final meeting, over 5,000 townspeople (1/3 of Boston’s population at the time) heard Samuel Adams say “Gentlemen, this meeting can do nothing more to save the country.” Legend has it that this was the signal for about 100 Patriots dressed as Native Americans to march to Boston Harbor and begin the Boston Tea Party.

Old South was such a symbol of Patriot dissension that during Boston’s occupation during the Siege of Boston (1775-1776), British troops ripped out the pews and pulpit and used them for fuel. It was filled with dirt and turned it into a riding school for the British Cavalry. After the war, it took almost eight years to raise the money to refurbish the Meeting House to make it usable as a place of worship.

Old South was almost destroyed in the Great Fire of 1872. Soon after the fire, it was soldand the congregation moved to Copley Square in Back Bay. Today it is a museum and one of the most important and interesting stops on the Freedom Trail.

Benjamin Franklin’s Birthplace

The site of Benjamin Franklin’s birthplace is just across the street from Old South at the location of the current 17 Milk Street. Ben was the eighth child of the ten children of Josiah Franklin and his second wife, Abiah. (Overall, he was the fifteenth of seventeen for Josiah.)

Today it is an office building.

Park Street Church – Freedom Trail Stop 3 Overview

Select your language to auto-translate:

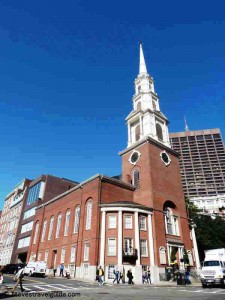

Bastion of Human Rights and Social Justice

Founded in 1809, the Park Street Church was built on the site of original town granary.

Free

Tours planned to restart the summer of 2023, please check the

website for information:

https://www.parkstreet.org/about-us/freedom-trail/

617-523-3383

Handicap access is via elevator and requires the staff to be alerted.

Public Transportation: Red or Green lines to the Park Street Station

Background Information

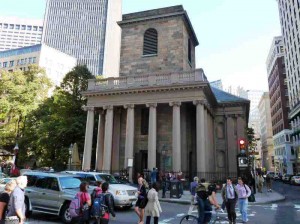

The Park Street Church is among the most beautiful in Boston, with its 217 foot steeple visible from many parts of the city. Its congregation originally spun off from the Old South Meeting House (Stop 8).

Park Street Church was designed by Peter Banner in 1809, who was inspired by Christopher Wren’s London churches. It held its first service in early 1810. Henry James called it “the most interesting mass of bricks and mortar” in America.

It carries the nickname “Brimstone Corner,” which may refer either to the fiery nature of the sermons or to the fact that gunpowder was stored in its crypt during the War of 1812. Brimstone (sulfur) is a major component of gunpowder along with charcoal and saltpeter.

Over the years the Park Street Church has been a bastion of social and missionary work. It was the site of one of America’s first Sunday schools (1816), the first prison aid society (1824), and early temperance society meetings (1826). The first missionaries were sent from here to Hawaii (1819). The church was the site of William Lloyd Garrison’s first public anti-slavery address in 1829. The song “America” (My Country ’tis of Thee) was sung publicly from its steps for the first time in 1831.

Old Corner Book Store – Freedom Trail Stop 7 Overview

Select your language to auto-translate:

Leading US Publisher 1833-64

Built in 1711 after the original house burned, under Ticknor and Fields, it was the nation’s leading publisher and produced works by Longfellow, Stowe, Hawthorne, Emerson, and Dickens.

It now houses a Chipotle Mexican Grill.

Background Information

The original house on this site belonged to Quaker Anne Hutchinson, who was banished from Boston in 1637. That house survived until 1711, when it burned in the first “Great Fire,” which consumed a major part of Boston, including Boston’s Town House (at the site of the current Old State House, Stop 9) and the Old Meeting House (Boston’s first Meeting House).

Soon after that fire, the current house was built by Dr. Thomas Crease to serve as both his residence and an apothecary. After several incarnations as a dry-goods store, residence and another apothecary, it became a bookstore and printing shop in 1828 when it was leased to Carter and Handee.

Five years later, in 1832, it was leased to publisher William Ticknor, who took in James T. Fields as his partner. Fields began editing a magazine called the Atlantic Monthly – printed on a printing press that was driven by two Canadian horses. The Atlantic Monthly is still published today.

The company’s greatest legacy was their development of the royalty system for authors. With this innovation, authors were able to share in the proceeds from their books sales for the first time. Prior to this, publishers purchased book rights for a set fee.

Ticknor and Fields was the nation’s leading publisher between 1833 and 1864. Among their authors were Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., Charles Dickens, and Louisa May Alcott.

During this period Ticknor and Fields was the regular meeting place for all the great writers of New England. It became known as “Parnassus Corner,” a reference to the mountain home of the Twelve Muses of Greek mythology.

The building was restored in 1960.

The Irish Famine Memorial

The Irish Famine Memorial commemorates the Great Irish Famine, which took place between 1845 and 1852. Many Irishmen and women emigrated to Boston during the famine, settling originally in Boston’s North End.

King’s Chapel – Freedom Trail Stop 5 Overview

ParagraphAdd BWS ShortcodeKing’s Chapel – Freedom Trail Stop 5

Select your language to auto-translate:

First Anglican Church in Boston

This church, built in 1754, was built around the original 1689 building so as not to disturb services. When completed, the original church was broken up and removed through the windows.

Summer:

This church, built in 1754, was built around the original 1689 building so as not to disturb services. When completed, the original church was broken up and removed through the windows.