Select your language to auto-translate:

“… just the right mix of content to make for a terrific tour…” David J. Asher “Saved me with visitors from the West Coast…” Steve S.

Download the free Apps – use with the Guide or by themselves when visiting the Freedom Trail!

The Freedom Trail Boston – Ultimate Tour & History Guide provides everything you need to bring your visit to The Freedom Trail to life. Use it to plan your visit, as a interactive tour guide, or even as a souvenir! Includes FREE STREAMING AUDIO NARRATION – a personal tour guide in your pocket (requires web access)!

The most comprehensive guide available, by far!

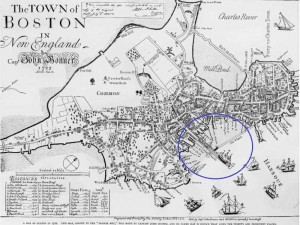

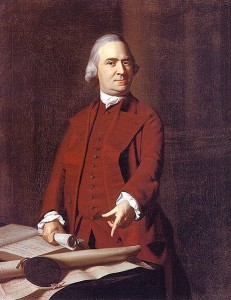

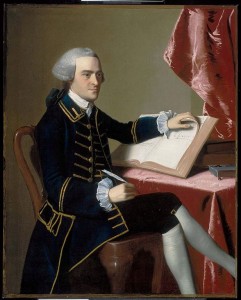

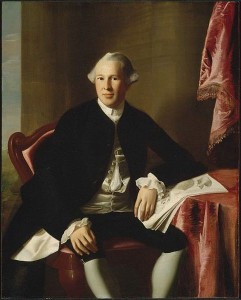

- Overview and detailed background information for all 16 Official and >50 Unofficial Freedom Trail Stops

- Side trips to Harvard Square/Cambridge, Lexington, Concord, Adams NHP, & Boston Harbor Islands

- Available in print or ebook formats.

- Print version retains ebook features with QR Code access to auto-translate and web materials

- > 70 photographs, maps and illustrations

- Auto-translate all major book chapters (with web-access) into Spanish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, Korean and more

- Access to additional free information including an interactive Google Map Tour, an Android app and iPhone/Pad app

- Budget tips including the best free guided-tours, where to find a bargain lobster, historic restaurants, and even a harbor cruise for $3 (children are free)

- Detailed itineraries for an hour, 1/2, full and two day visits. Learn exactly what to visit with your limited time

- Child-friendly and family-oriented tips

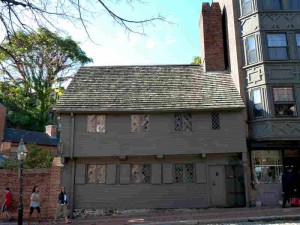

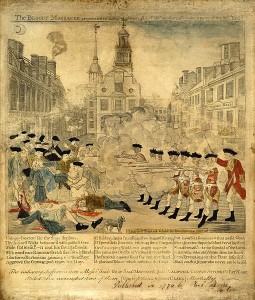

- Descriptions of all the events that bring the Freedom Trail to life including the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party, Paul Revere’s Ride, the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and the Battle of Bunker Hill – more than is provided by any other tour guide