Select your language to auto-translate:

One of the great frustrations in publishing an eBook is that the publisher is megabyte constrained – e.g., there is an incentive to keep eBooks small.

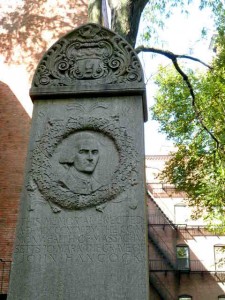

High resolution photos use up a lot of megs. So, to keep things small, the photos in the eBook are either 800 x 600 or 640 x 480 and have been compressed. They are illustrative and fine for an eReader, tablet or phone, but this resolution does not do them justice as photographs.

The gallery below contains the photos used in the “Freedom Trail Boston – Ultimate Tour & History Guide – Tips, Secrets & Tricks” eBook in 2048 x 1536 format compressed to +/- .5 meg each. I’ve also include a few pictures that simply did not fit or that are representative of what you will see on and around the Freedom Trail. If anyone is interested in one in native format, 4000 x 3000 +/- 5 meg each, email me and we’ll figure something out.

Warmest regards,

Steve