Select your language to auto-translate:

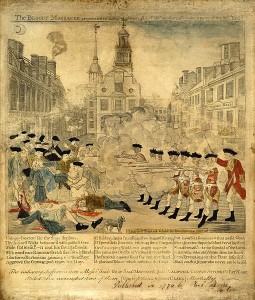

One of the most fascinating and overlooked aspects of Boston is how much the land-form has changed over the years. What you experience today is over 50% landfill. Places you walk, such as the area around Faneuil Hall, were actually part of the harbor when Boston was founded in 1630.

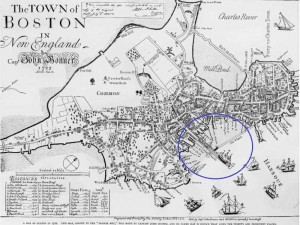

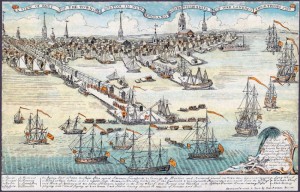

When the first visitors arrived, they found a salamander-shaped, rocky, hilly, peninsula that was formed by erosion at the end of the last ice age. Called Shawmut by the Native Americans, it was small, two miles long and only a mile wide. It’s only connection to the mainland was the low-lying, narrow, wind-swept Boston Neck, which often flooded at high tide and was impassable during stormy weather – meaning the peninsula became an island. During the siege of Boston, the British troops were effectively blockaded into this tiny island, without adequate food or firewood.

The peninsula was dominated by three hills, hence its early name of Trimountaine, which was later shortened to Tremont – a name that lives on in today’s Tremont Street. There was Copp’s Hill (in the North End), Beacon Hill (which had three summits and was almost twice as high) and Fort Hill (which was located in today’s financial district).

[embedplusvideo height=”365″ width=”450″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/y3QlGzJW27c?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=y3QlGzJW27c&width=450&height=365&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep8086″ /]

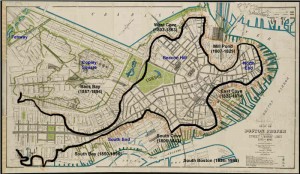

Today’s Boston was created by a series of land reclamation projects, which started in a small way soon after the Puritans arrived in 1630 (you can see the 1630 water line marked in the pavement near the Samuel Adams Statue behind Faneuil Hall).

The major landfill projects took place between 1807 and about 1900, although some reclamation projects extended until almost 2000. Much of the land for the early projects came from the leveling of Fort Hill and from Beacon Hill. The largest project, the filling in of the Back Bay took, spanned several generations between 1856 and about 1894. For that project, gravel was transported in on a specially built train line from Needham, a suburb about nine miles away. One of the first of the second generation steam shovels was used to fill the gravel cars for the trains, which ran around the clock for almost fifty years.

For a fantastic website, which was used to create the animations in the video above, visit the Boston Atlas. It is simply the best place to play with Boston’s changing topography, and was a great source for this post. Also visit the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library – a wonderful source of historic Boston maps, many of which were used in the creation of this post and the accompanying video. For those interested in learning more, there is another interesting post from Professor Jeffery Howe at Boston University; for that post, click here.